Giant Groupers: ambassadors for reef conservation, flying to new homes across America.

Giant Pacific Grouper at our research facility in Kona, Hawaii. Photo Jeff Milisen

The Giant Grouper (Epinephelus lanceolatus) is possibly the rarest coral reef fish in the Pacific. This fish grows up to almost 1,000 lbs, but it has been so heavily over-fished throughout its native range (Hawaii, and the Indo-Pacific region), that it is now listed as “Vulnerable” (one step from “Endangered”) on the IUCN Red List[1]. The last reported sighting of this species from the Island of Hawaii was over 5 years ago.

Kampachi Farms – and our forebear, Kona Blue – have been rearing Giant Grouper at our Kona research facility since 1999. Because of the scarcity of these fish in local waters, we originally imported fingerlings from a hatchery in Taiwan, and grew them out until they started spawning … and they kept growing! Some of these fish are now over 18 years old, and weigh perhaps 300 pounds (But that’s just a guess … we don’t have any scales that can weigh fish this big!). And they are still growing!

Juvenile E. lanceolatus. Photo Jeff Milisen

The original intention was to try to raise these high-value groupers for commercial culture. However, this proved unfeasible for two reasons. Firstly, fish this big are very difficult to spawn. We have not obtained a viable spawn from these fish since 2012. We believe that the problem is that their tanks are too small, and they are not able to perform the courtship rituals that precede spawning. The second problem is that we were unable to wean the juveniles onto a more sustainable pellet diet. This meant that commercial culture of Giant Grouper would require a constant supply of sardines or squid to feed the fish, and that simply doesn’t work – either economically, or ecologically. We want our fish culture to soften humanity’s footprint on the seas, not to exacerbate it!

So – if not commercially valuable, we thought these fish might be valuable for conservation. We therefore requested permission from Hawaii state authorities to restock these fish onto Hawaii’s reefs, where divers could see them in their native habitat. However, some were concerned that these fish might be genetically distinct from the native Hawaiian population, and with no native fish to compare to our own, this proposal was scrapped.

So what to do? These fish have always been the “star of the show” for our research site tours and other outreach activities. They have served as fantastic ambassadors for reef conservation to the 6,500+ visitors who have toured the Kampachi Farms facility over the past few years. We have learned a lot from these beautiful fish, and their offspring, which were spawned and raised on-site by the research team. However, there comes a time when we have to say goodbye to those that we love … and it was that time for our Giant Groupers. But what to do with a 300 pound fish friend? The answer was to fly, not fry!

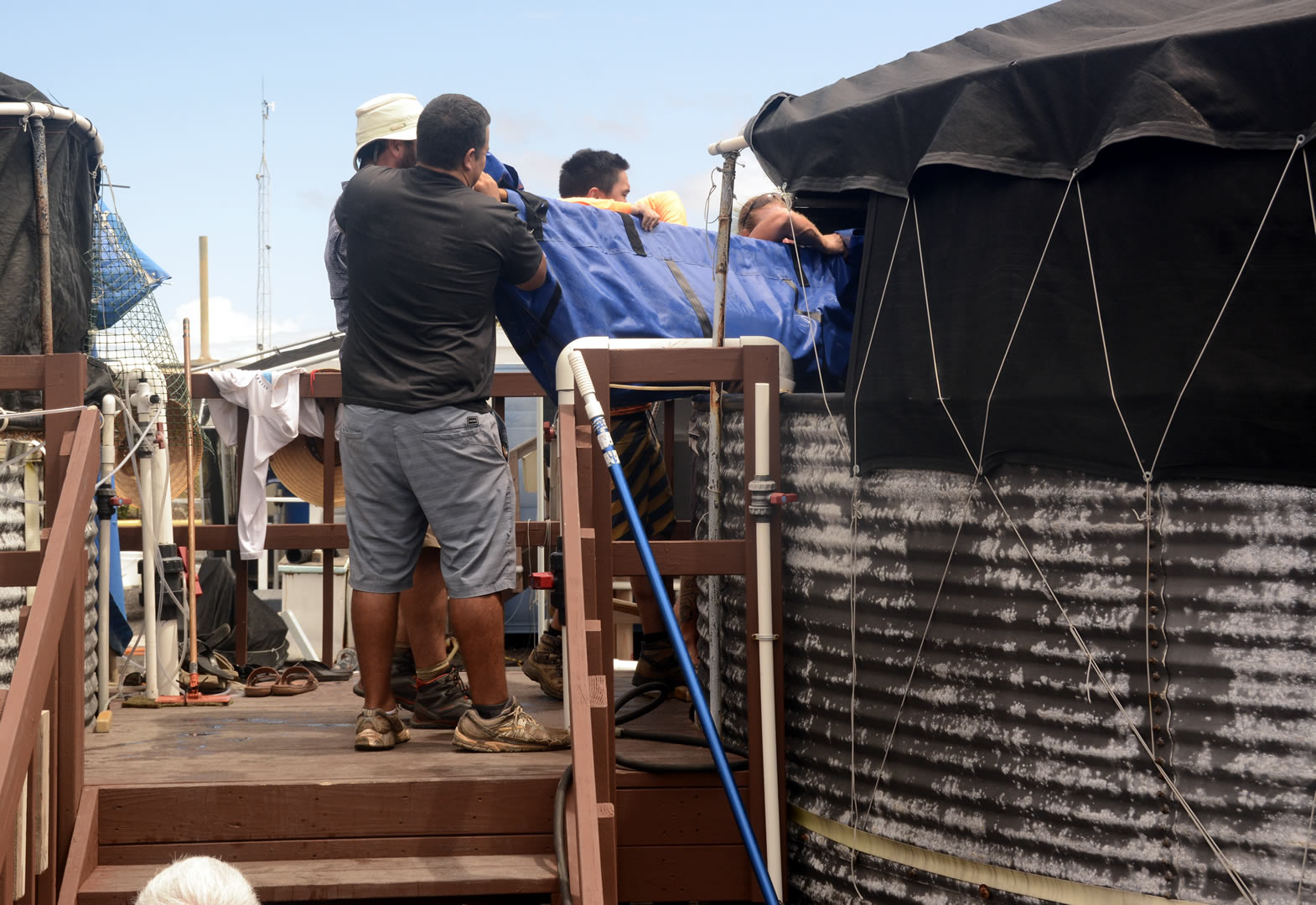

With the help of a very talented team of acquisition specialists at Reef and Ray, we are happy to announce that we have found new homes for our Giant Grouper. We have donated these fish to a number of aquariums throughout the United States, where they will be able to carry on their work as coral reef ambassadors, and live out their days in comfort, with other coral reef fish communities to keep them company. Over the past few weeks, twelve of our Giant Groupers have been sent to aquariums in Hawaii, Missouri, Indiana, and even as far as New Jersey. Our oldest and largest specimen (appropriately named “Hulk”), will be traveling to the Adventure Aquarium in Camden, New Jersey.

It has been a great joy and an honor to raise these magnificent fish. We wish them all long and enjoyable lives in their new homes! We’d also like to extend great thanks to all of the aquariums for adopting our Giant Grouper, where they will now connect with a broader audience – exemplifying the treasures of our precious ocean environment and our collective duty for preservation. Please stay tuned for updates as they arrive at their new aquariums. Follow our grouper updates on twitter @kampachifarms.

[1] The International Union for Conservation of Nature - assessment of the species Epinephelus lanceolatus - last assessment carried out in 2006 http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/7858/0

Why is There No Commercial Mahi-mahi Aquaculture Yet?

Mahimahi (Coryphaena hippurus), also known as Dorado or Dolphinfish, is a tropical oceanic predator. In the U.S., it is a prized sportfishing species with an annual recreational landing of approximately 5,000 tonnes in recent years; and it is in even higher demand commercially, leading the U.S. to import 25,000 tonnes in 2013 (1). Keep in mind these numbers are for the U.S. alone.

One of the reasons wild stocks have been able to endure this fishing pressure is the remarkable growth and reproductive capabilities of this species. Juveniles have been shown to gain roughly 30 grams a day in laboratory settings, and grow up to 9.5 kg in the first year (2,3). Perhaps more importantly, they reach sexual maturity in just 4 to 5 months in the wild and spawn up to 180 days of the year (4)!

The market, the growth rates, and the success in captive spawning are all there; so why is there no mahimahi aquaculture? The Achilles heel for C. hippurus thus far is their natural aggression: larval rearing can be challenging due to high rates of cannibalism at early life stages, followed by territorial bloodlust as they reach maturity. They start earning the moniker “dolphinfish” at a young age, exhibiting the ability to jump impressively high out of things (tanks) or into things (walls).

At Kampachi Farms we strive to allay this aggression by creating cohorts of single sex mahi. The sex of several other marine fish species can be determined by unique temperature fluctuations near time of spawning, and anecdotal evidence suggests this can be applied to mahi. By defining the ideal water temperature and timing/duration of exposure, we could provide a noninvasive, economical method of producing all-male cohorts. This would be ideal for aquaculture as male mahi aggression is naturally lower in the absence of females, and the overall growth rate of males is higher as they invest less energy in reproduction.

While mahi may be excellent restaurant fare, they are also incredibly useful for ecological research. The same biological features that make this a promising species for commercial production – exceptionally high metabolism, low age at reproduction – make a convenient proxy to illustrate the effects of environmental changes on marine finfish. The University of Miami has used their renowned C. hippurus spawning program in myriad studies since the Deepwater Horizon oil spill to observe the developmental effects this event may have had on pelagic fish species (spoiler: oil is not great for fish). Since mahi progress through their developmental stages so quickly, it is an ideal species in which to study toxicology. For instance, certain levels of embryonic exposure to crude oil may prove nonlethal, but may impact cardiac function and energy demands of the fish later in life (5,6). Similarly, mahi have been used to illustrate the metabolic and behavioral impacts of ocean acidification (7). This knowledge can be applied to past and future scenarios to better understand long term impacts of anthropogenic activity on fish population fitness.

Wild mahi have thus far proven robust to fishing pressure, but the world needs ever more seafood. Optimizing aquaculture of this species can increase availability, alleviate pressure on wild stocks, as well as provide invaluable knowledge for resource management in the face of a changing environment.

More mahi for all!

References:

- NMFS Recreational Fisheries Statistics Queries (2013). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association. [online] Available at: https://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/st1/recreational/queries/ [Accessed 21 Nov. 2017].

- Hagood, R.W., Rothwell, G.N., Swafford, M., Tosaki, M. (1981) Preliminary report on the aquaculture development of the dolphin fish, Coryphaena hippurus (Linnaeus). J. WorldMaricult. Soc., 12(1), pp.135–139.

- Kraul, S. (1989) Review and current status of the aquaculture potential for the mahimahi, Coryphaena hippurus. Advances in Tropical Aquaculture, Workshop at Tahiti, French Polynesia, 20 Feb-4 Mar 1989.

- McBride, R.S., Snodgrass, D.J., Adams, D.H., Rider, S.J. and Colvocoresses, J.A. (2012) An indeterminate model to estimate egg production of the highly iteroparous and fecund fish, dolphinfish (Coryphaena hippurus). Bulletin of Marine Science, 88(2), pp.283-303.

- Esbaugh, A.J., Mager, E.M., Stieglitz, J.D., Hoenig, R., Brown, T.L., French, B.L., Linbo, T.L., Lay, C., Forth, H., Scholz, N.L. and Incardona, J.P. (2016) The effects of weathering and chemical dispersion on Deepwater Horizon crude oil toxicity to mahi-mahi (Coryphaena hippurus) early life stages. Science of the Total Environment, 543, pp.644-651.

- Pasparakis, C., Mager, E.M., Stieglitz, J.D., Benetti, D. and Grosell, M. (2016) Effects of Deepwater Horizon crude oil exposure, temperature and developmental stage on oxygen consumption of embryonic and larval mahi-mahi (Coryphaena hippurus). Aquatic Toxicology, 181, pp.113-123.

- Pimentel, M., Pegado, M., Repolho, T. and Rosa, R. (2014) Impact of ocean acidification in the metabolism and swimming behavior of the dolphinfish (Coryphaena hippurus) early larvae. Marine biology, 161(3), pp.725-729.