Save a tuna, eat a vegetarian

Seafood has a smaller carbon footprint than any other animal protein (Nijdam et al, 2012). But just like every other kind of meat, the higher the trophic level, the higher the energy input to make it.

For seafood, low trophic level typically means filter-feeding bivalves, such as oysters, or forage fish, such as sardines or mackerel. Most consumers will agree that an ahi fillet is more desirable than a plate of mussels or jellyfish. But what if you could have a hearty, satisfying fillet – sashimi-grade for the poke-lovers – that was also an herbivore? Enter Kyphosidae. At Kampachi Farms we have been working with Kyphosus vaigiensis, an herbivorous reef-fish with a longstanding presence in Hawaiian cuisine.

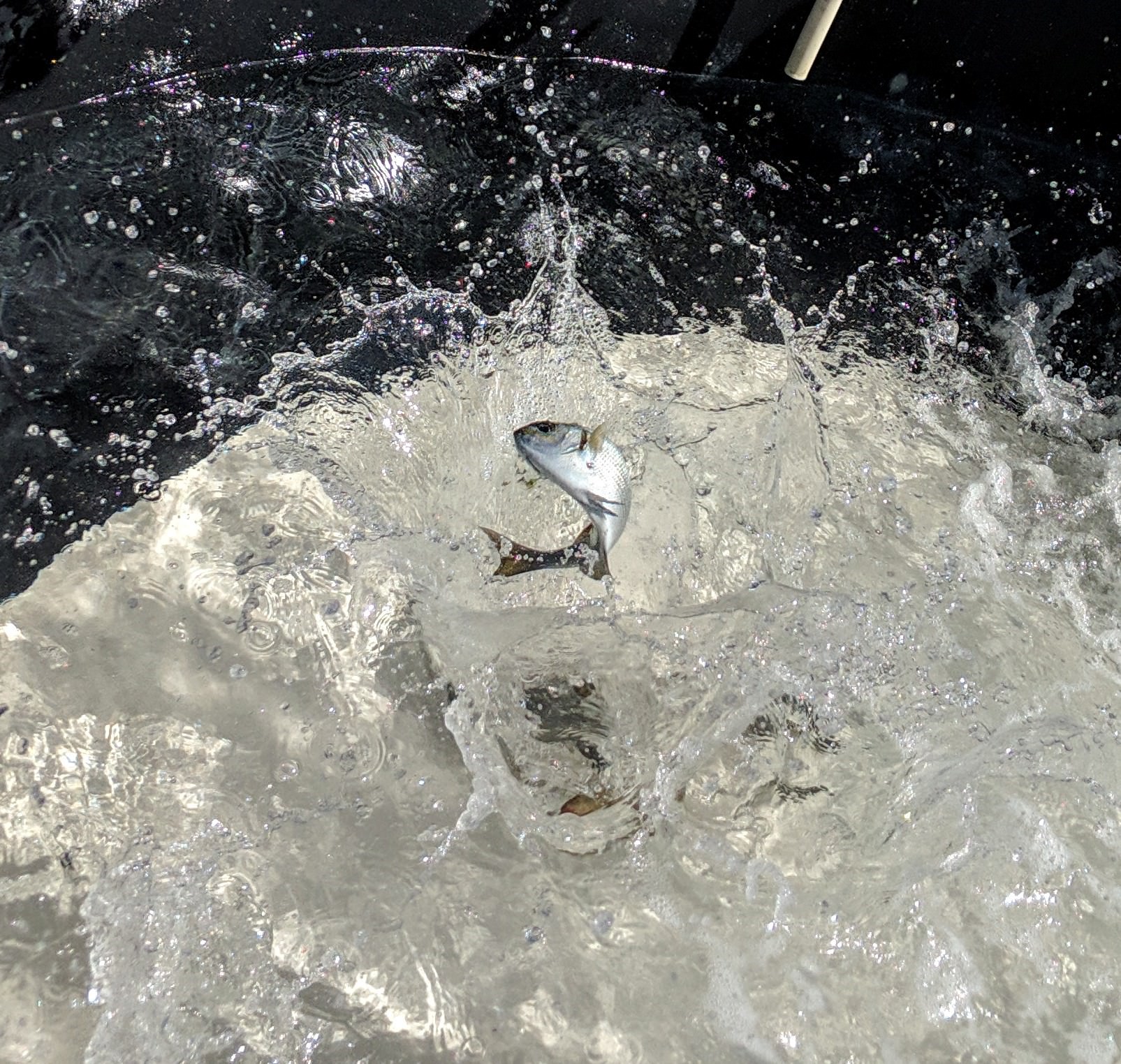

Kyphosid from local Kona waters; a commonly fished for species, popular as poke. He ded.

This fish is known as enenue or nenue in Hawaiian (rudderfish or sea chubs in Not Hawaiian), and in some regions was regarded as a prized reef fish, reserved for ali’i (royalty) only (Ulukua, 2019). Nenue are found in abundant schools around Hawaii; 2-3-kilogram fish are common, while state records exceed 4.5 Kg. One of the traditional preparations for nenue was poke – a staple of native Hawaiian food, originally consisting of raw reef fish, sea salt, limu (seaweed), and kukui nuts. Poke recently exploded onto the mainland United States fast-food scene; it can be found at myriad stand-alone poke counters as well as at the likes of Red Lobster and The Cheesecake Factory (Dixon, 2016). While Hawaiian poke was traditionally made of a variety of fish, including nenue, the versions in vogue now are based almost exclusively on tuna or salmon, two high-trophic predators.

Nenue have a number of advantages as a candidate for aquaculture. Our research at Kampachi Farms thus far has found that adult nenue spawn readily in captivity. Larvae are exceptionally hardy in preliminary hatchery efforts. Our colleague Syd Kraul at Pacific Planktonics recently raised a final total of 200 baby nenuitos from a small sample of our captive-spawns, in an extensive ‘green-water’ culture system. We are planning larger-scale runs in our research hatchery in the near future. Nenue also have ctenoid scales, with a rough texture and row of tiny teeth at the edge; this armor dramatically aids in ectoparasite resistance.

Their most interesting feature, however, is their guts.[1] Nenue have a unique digestive system that allows them to graze on macroalgae. They subsist on seaweeds by using fermentation in the gut to break down the complex carbohydrates of limu. Several rounds of grow-out trials with juveniles have shown that they can thrive on diets based on aquatic plant material as well as corn and wheat. Herbivory precludes the need for wild-caught forage fish – reducing the overall ecological footprint – and perhaps renders them better suited to small-scale fish farming in less-developed countries.

Hand-model displaying juvenile Kyphosus vaigiensis, also known at this stage as nenuito.

26 day-old Kyphosus vaigiensis learning their numbers.

Between ready acclimation to captivity, routine marine fish larval rearing, parasite resistance, and a broad plant-based diet, this fish has all the trappings of success in sustainable aquaculture. And it yields poke-quality meat to boot!

At Kampachi Farms we believe that seafood is healthier for people and healthier for the planet, compared to other types of meat. But one should always strive for improvement: we can improve seafood sustainability by diversifying what we eat and prioritizing low-trophic species in this diversification. Legions of researchers are pursuing plant-based and alternative proteins that can suitably nourish those carnivorous fish the market so demands – a noble pursuit, yet an admittedly roundabout way to produce ‘low trophic’ species. The more direct way, the simpler way, is to culture natural marine herbivores. Not all marine herbivores are suited for the dinner table. And market favorites – such as ahi, snappers, and our King Kampachi – are all beautiful food fish in their own right. However, if even a fraction of the restaurants selling salmon and ahi poke bowls today also offered nenue grown on herbivorous diets, the seas would be that much better for it.

A flippin’ cute nenuito !

References

Dixon, Vince. 2016. Data Dive: Tracking the Poke Trend. www.eater.com. Citing FourSquare.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2018. American seafood industry steadily increases its footprint. www.noaa.gov.

Ulukua: The Hawaiian Electronic Library. 2019. Native use of fish in Hawaii. Mok. 2 Descriptive list of Hawaiian fishes (‘Ao’ao 56-163).

In-text links to…

https://oceana.org/blog/eating-seafood-can-reduce-your-carbon-footprint-some-fish-are-better-others

https://www.sbs.com.au/food/article/2018/02/01/jellyfish-if-you-cant-beat-them-eat-them

http://www.hawaiifishingnews.com/records.cfm

[1] Stay tuned for future blog posts about our imminent research on the kyphosid gut microbiome and its potential application to biofuel production.

Hooked on Aquaculture: Interview with Kampachi Farms’ Interns

From left to right: Travis Burroughs (intern), Julien Stevens (internship coordinator), and C.J. Chao (intern).

As the Internship coordinator at Kampachi Farms, I regularly field emails and calls from marine scientists in training, and aspiring fish farmers. I myself started out at Kampachi Farms as an intern, and I’m a firm believer in the opportunities that volunteering can provide. It’s a great way to gain aquaculture experience, and to get to know an organization without having to commit yourself for the long term. But often potential aquaculture interns have a romanticized notion about what their role might be. To clarify what the role is all about I’ve asked our two summer interns, C.J. and Travis, to answer a few questions.

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and why you wanted to intern at Kampachi Farms?

C.J. Chao: I’m a senior at Boston University studying Environmental Policy and Analysis. I came to Kampachi Farms because of my great interest in aquaculture, which stems from my love of the ocean. I look at aquaculture as a possible sustainable substitute for depleting wild fisheries and want to be involved in an industry that is new, progressive and exciting. I’m originally from San Francisco but grew up in the suburb of Marin. I’m a certified master scuba diver and also maintained saltwater aquariums as a kid. These two hobbies fostered my interest in the aquaculture field.

Travis Burroughs: I’m from Larkspur, California, and am a senior at the University of Denver studying sustainability and marketing. My interest in aquaculture was sparked by my lifetime of fishing, which first led me to an internship at Monterey Abalone Company last summer. I had a fantastic experience there and with my love of fish, I wanted to gain work experience with a company that focuses on environmentally responsible fish farming.

What sort of work did you do during your internship at Kampachi Farms?

Travis: The internship was both full of routine experience and novel challenges, depending on research needs. These routine tasks included: feeding fish, observing behavior, scrubbing tanks, maintaining the filter systems through back flushing and cleaning filters, and tidying up the site. We also helped to move 20 tons of gravel to level the site for new broodstock tanks for our kampachi.

CJ: Each day Travis and I would complete necessary husbandry tasks, including feeding fish and cleaning tanks. We also assisted with ongoing experiments, including a feed trial using an experimental soy-based feed, and testing the viability of growing algae in the open ocean for human, animal feed, and biofuel purposes.

What did you learn from your internship?

CJ: Kampachi Farm’s research team offered me a wide ranging and in-depth look into research-oriented aquaculture. During my internship I was able to work with many farmable marine species, including Seriola rivoliana (also known as Kampachi or Yellowtail Amberjack), Giant Pacific Grouper, Nenue (Grey Chub) and several species of algae.

Travis: While at the Kampachi Farms R&D facility in Kona we were given a first-hand look into fish husbandry at the different life stages. We were lucky enough to be on site during a feed trial, where over 700 fingerling kampachi that had been spawned and hatched out on site, were being grown out on different sustainable feed options. We began feed trials with fish ranging in size from 14-40 grams, which involved weighing, measuring, and tagging each individual fish and then putting them into marked tanks. The goal of the feed trial was to compare different feeds and see which one produced the best FCR and overall fish health. The data collected on-site could then be used in future commercial use with Kampachi Farm’s King Kampachi in La Paz Mexico.

Some of the Kampachi Farms research team with C.J. and Travis on their last day.

A few considerations to keep in mind for potential interns: All of our research work in Kona is grant-funded, and so we are presently unable to pay interns for their time. Any internship would therefore need to be on a pro-bono basis. Feel free to get creative in your self-funding options; we have had students find outside funding from their University or regional STEM internship programs. Interns are required to provide their own housing and transport to Kona, and must also have reliable ground transportation when here on the island (public transport in Kona is virtually non-existent).

We love hosting passionate aquaculture interns when our research schedule allows it. If you are interested, please contact our team to learn more about our internship program. You can also stay up to date with our current research projects here.